Walking away from a wrongfully imprisoned detainee. Watching as a family with children is evicted. Refusing services to a woman experiencing domestic violence. Leaving a child in long-term asylum detention. Standing by as a torture victim is deported back to their country of origin.

In the human rights field, these experiences are more common than not. Most, if not all, of us remember a time when we were forced to do something we wish we could undo; those experiences we try to wash away, gloss over, relegate to the dustbin of our minds as soon as they happen. In this work, we’re often called to do things that wrench our guts. Make us feel complicit. Leave us with a sense of being tainted. Make us question, “How can I feel so guilty? How could I do that when all I wanted was to make the world a little better?”

One that sticks in my mind was closing the door as I left the forensic psychiatric ward where a young trans person I had just interviewed was being regularly tortured. They were so over-medicated they couldn’t sit up straight to speak with us, although they tried hard. They smiled, chatted as much as they could. They were polite, sweet and delighted to see us. We visited after receiving a complaint detailing how, every day, they were being subjected to severe physical and psychological coercion, violence and control. There was no doubt in my mind as I waved goodbye and left them there that the abuse would continue that same day. Yet I left. There was physically, practically and legally nothing else I could do. We took them on as a client and were able to help improve their situation somewhat in the long term. But, in that moment as I closed the door, I was utterly powerless to help them as I walked free.

In most organisations, we debrief these situations and move on. We may spend an evening drinking with colleagues and railing against the system – yet again. We sleep it off and pick up a new case file in the morning. But there is a word for these experiences that, despite nearly two decades in human rights, I had never heard until last year. It’s what’s called a moral injury: a specific type of psychological trauma that is poorly understood and even more inadequately supported.

Moral Injury

A moral injury is when you are forced to do, see or experience something that fundamentally goes against your values, your sense of what is right. You just cannot feel justified about it in your heart, even though you may have had no choice. It violently offends your conscience. And it can leave a deep soul wound, scoring a painful imprint on our sense of ourselves and of the world.

Although much of the literature on moral injury incorporates a spiritual or religious dimension, it is not intrinsically a spiritual or religious concept or experience. Everyone holds a set of personal and professional values, and moral injury is relevant whenever these are violated – whether they are secular or religious values.

Most research and discussion on moral injury has taken place in the context of war where combatants witness or commit atrocities such as rape, or murder of civilians. In the last three years, covid has generated considerable awareness of moral injury as a form of trauma for frontline workers: At the height of the pandemic, health care personnel were forced to choose which patients to treat and which to let die. Overflowing capacities meant that people with life-threatening illnesses or injuries had to be turned away.

Research has also looked at moral injury in the workplace in the context of journalists covering the 2011 Norway terror attack; teachers exposed to community violence in El Salvador; veterinarians (who, for example, perform euthanasia); and police officers who have killed people.

Moral injury has been described as occurring “when you have a vision of the world as fundamentally fair and good and something you’ve done or witnessed destroys that vision.” Those who enter the world of human rights advocacy are often driven by a vision of a more equal, just world. We tend to believe that there are universal principles of good that need to be expanded to include marginalised or oppressed groups, those who are othered and abused. From this perspective, it seems likely that human rights advocates are particularly vulnerable to experiencing moral injury.

Yet, there has been almost no research on the prevalence of moral injury in this community. One 2017 research paper found that moral injury in this group is associated with PTSD symptom severity. In other populations, moral injury has been associated with psychological distress and burnout, depression, suicidality, and anxiety. And it is no coincidence that human rights advocates report levels of PTSD, depression and burnout that are similar to those for first responders and combat veterans.

In addition, there is increasing discussion of the potential for moral injury arising from workplace practices in situations where the nature of the work itself is not particularly stressful or demanding. These may include events such as being forced to fire a good employee, participate in workplace bullying or discrimination, or witnessing or participating in the ongoing exploitation of a colleague who is burnt-out or otherwise struggling.

In my experience working for and in partnership with dozens of human rights organisations on every continent, what we now understand as moral injury is routinely considered to be ‘just part of the job’ for human rights advocates. Yet, I believe it is a significant driver behind the high rates of burnout, career drop-out and low staff retention. And it is exacerbated by the still widespread, old school attitude that venerates the ability to ‘ignore’ and ‘move on’ from such experiences. It thrives in (all too common) organisational cultures that denigrate those who can’t simply compartmentalise what they have experienced and get on with the work; that stigmatise them as weak, unsuited to human rights advocacy or, in the worst cases, a liability to their colleagues and clients.

So, what can we, as individuals, do?

There are no ‘top ten hacks for beating moral injury’ and, even if there were, I’m not a fan of those sorts of approaches where emotional or psychological distress is involved. We humans just don’t work like that. Our experiences are complex and individual, and so must be the solutions. Moral injury is a type of identity crisis that requires coming to terms with the existence of real cruelty and suffering in the world in a way that still allows us to find purpose and joy.

For these and other reasons, it’s important not to do this work alone. Community and connection are the best antidotes to the isolation, shame, guilt and emotional distress that can arise from moral injury. As a rule, family and friends cannot possibly understand the reality of human rights advocacy, and the associated moral injury or other traumas. But peers – especially peers trained in trauma – can afford a valuable opportunity to discuss the subject safely with someone who ‘gets it’.

That said, there are some basic places to start working with this sort of distress:

- Ask yourself unflinchingly whether you may have experiences that have grossly transgressed your values and conscience. Identifying and naming them is a prerequisite to addressing them.

- Inquire about your organisation’s trauma-related policies, procedures and supports.

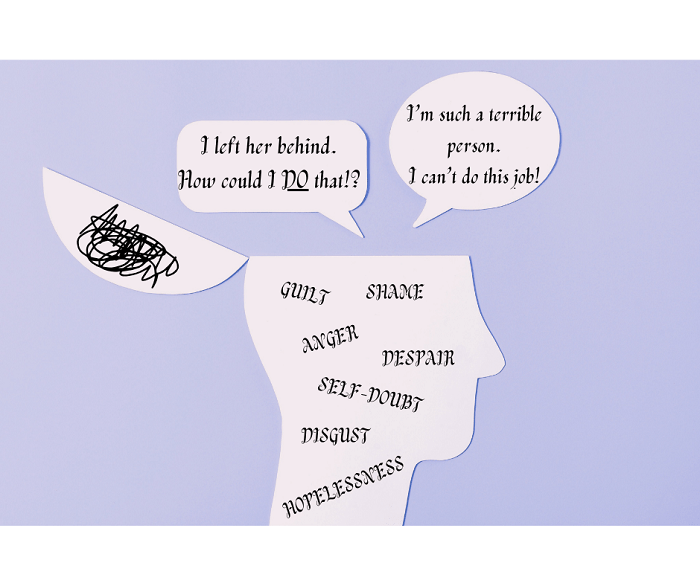

- Remember that shame, guilt, anger and disgust are normal reactions to the impossible situations you’ve faced. You are not a bad human. You have not failed. You are not under-performing. You are simply in a hard job, likely without the knowledge and support you need.

- You may be experiencing:

- Anxiety

- Depression or despair

- Burnout

- Overwhelm and hopelessness

- Sleeplessness

- Even anger, aggression, and irritability.

These are common reactions to moral injury. You are not ‘mentally ill’. You are not ‘suffering from a mental disorder’. You are struggling with massive dissonance between who you are, your values and beliefs, and the reality of working with human rights violations.

- Talking it out is not always enough, especially to overcome the impacts of trauma. Identifying other modalities that may help, such as bodywork or nervous system regulation practices, is an integral part of regaining your resilience.

What about organisational leaders? What is our role in preventing and managing moral injury?

If you are a leader in your organisation, you are likely aware that human rights work is inherently fraught with ethical challenges that are outside your control. In that sense, it really is just part of the work because we are fighting to change harmful systems that, by their very nature, expose advocates to trauma, suffering, the risk of overwhelm, and feelings of helplessness. Adding a budget line for staff therapy is not going to be enough to counteract this. To support employees, improve staff retention, and facilitate effective work, it is usually necessary to overhaul the organisational culture and consciously embed trauma-informed practices and procedures across the board. This can be a sensitive and challenging process. It is imperative that it is initiated from a well-informed foundation and, ideally, with the support of a trained, experienced expert. That will help avoid pitfalls and maximise the benefits for staff, the organisation, clients and yourself.

Broadly, a sound process for beginning this shift in culture and practice may look something like this:

- Ask yourself honestly whether you and your staff are exposed to moral injury in the course of your work.

- Educate yourself on trauma-informed leadership.

- Open dialogue (in a trauma-informed way) with your staff about their experiences of advocacy, difficult or confronting situations they’ve faced, and the impact these have had.

- Consult your staff on the supports that are, or need to be, available around moral injury in their work.

- Conduct a trauma-informed evaluation and review of your organisational policies and procedures, especially budget, financial processes, training and development policies, M&E, and human resource policies.

- Identify your organisation’s capacity to take action based on the evaluation and review, including financial capacity.

- Develop and implement a feasible plan to address gaps, and strengthen your proactive and reactive strategy.

That young trans person lives in a permanent place in my brain, together with all the other clients like them that I’ve encountered over the years. I’ve been lucky to find many different types of support, and to study and work through trauma’s impact for myself. My heart still aches for the unaddressed injustices and pain. I don’t think that ache ever really goes away. And I’m not sure I want it to because it reminds me of my humanity in a brutal world. But understanding my role in these situations and my responses, and developing strategies for resilience has helped me to no longer be haunted by them. Instead, they fuel my drive to redress the balance in whatever ways I can, including by supporting others to continue fighting for equality, justice and reparations. These experiences no longer overwhelm and exhaust me; now, they strengthen my resolve.

Support from trained peers has proven to be particularly effective in addressing moral injury. Peer support is the foundation of trauma recovery coaching as I practice it. If moral injury is something that resonates as an experience in your life as an advocate or organisational leader, please don’t hesitate to reach out.

Ann Campbell BCL, LL.M, CTRC is a trauma trained coach certified with the International Association of Trauma Recovery Coaching. Prior to coaching, she spent almost two decades as a human rights lawyer in Ireland and internationally.

Copyright © 2023 Ann Campbell. All rights reserved T&Cs, Privacy Policy

Very interesting and well-written article.

LikeLiked by 1 person